Automata-Based Programming With Petri Nets - Part 1

Petri Nets are extremely powerful and expressive, but they are not as widely used in the software development community as deterministic state machines. That’s a pity - they allow us to solve problems beyond the reach of conventional state machines. This is the first in a mini-series on software development with Petri Nets. All of the code for a full feature-complete Petri Net library is available online at GitHub. You’re welcome to take a copy, play with it and use it in your own projects. Code for this and subsequent articles can be found at __http://github.com/aabs/PetriNets_. _

I didn’t realize, but there’s a paradigm for what I’ve spent the last few years doing: Automata Based Programming. Despite the warm glow of knowing I work within a really cool (not to mention venerable) paradigm, I’ve come to realize there are flaws in how I used my automata. I’ve been exploring the possibilities of Petri Nets with a view to overhauling my DFA based systems.

Every week, I’m asked for the code of a state machine system I blogged about a few years back. I no longer have a copy of the code I used in that post, and I no longer recommend the models I used anyway. It was based on Deterministic Finite Automata (DFAs), C# and T4 templates. I’m revising the approach I used in ‘06 in favour of a more powerful one based on High Level_ Petri Nets_. In this series, I’ll look at the benefits and pitfalls of the techniques I used and suggest better alternatives. This time, I’ve made the code permanently accessible via GitHub. I’d welcome feedback, feature requests and collaborators.

Notes from the trenches

Since 2008, I’ve been developing a cloud-based soft-phone product - Skype for call-centres if you like. Under the hood, it models what’s going on using state machines very like the ones in my post mentioned earlier. Most of the inputs to the state machines are event notifications from telephony hardware. In addition to tracking call workflow, they track the lifecycles of daemons and threads. For a typical user session (of which there may be hundreds or thousands at a time) it maintains a dozen different state machines modelling some aspect of the session. It is clearly an automata-intensive application, and it’s important to me that there are no hidden flaws or vulnerabilities in the core of the app.

The current automata models have worked out really well, yielding a massive dividend in reliability. That said, the way we used our DFAs is vulnerable to consistency errors without explicit protection. The vulnerability stems from our wish to factorise the state machines into orthogonal DFAs each modelling some independent aspect of the user’s session. We do it because it makes the state modeling more tractable.

The issue with ‘factorising’ the state model is that having multiple _independent _DFAs increases the state space, allowing the system to legitimately assume invalid state combinations. We have a dozen state machines with an average of 8 states each. The total state space would be about (about 69 billion) states. Practically all of those states are invalid, and it’s the job of the supporting architecture to ensure that invalid states are avoided. Naturally, one avoids invalid state combinations by accurately choosing the correct result state even in the face of faulty communications, hardware, user input and programmer errors. That’s no mean feat at the best of times, but especially hard in a real time event driven system hosted on a widely distributed hardware platform.

After a couple of years, we’ve pretty much done that, but we had no assistance from the state models themselves. I want an automata based model that will _inherently _prevent invalid states but still be comprehensible to the telephony domain experts who produce the state models.

For the sake of brevity I’ll ignore the other reasons why I believe Petri Nets are better able to deliver guarantees of consistent states. I’ll come back to those other reasons in subsequent posts, where I will discuss some alternate ways to implement a Petri Net and the relative benefits of the different representations. For now, I’ll just remark that a Petri Net provides a means to veto transitions allowing us to add consistency control to a model. It’s also Turing Complete where DFAs are not, but I’m not sure whether that’s a practical distinction worth making or not.

I suspect most readers are more interested in how Petri Nets work, and how to use them to model their applications, than with the theoretical distinctions between the computational capabilities of different types of automata. There are many papers and books demonstrating Petri Nets are more expressive than DFAs. The question for me was – are they better in meaningful ways? I’d already had great successes with DFAs; is there a way that the richness of the Petri Net model can enhance what I’ve already got. I hope to explore the answer to that in the posts that follow this.

I’m also not going to delve too deeply into the extensive body of theoretical literature out there. I’m more interested in the scarcely explored problem of how to utilize Petri Nets to solve problems in software engineering. I especially want to work out some of the design principles of event driven applications using Petri Nets.

I’ll start with what Petri Nets are, then in subsequent posts I’ll move on to show a couple of ways to represent them, the trade-offs of different representations and then how to to drive an app using Petri Nets.

What is a Petri Net?

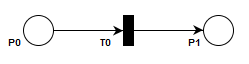

A Petri Net is a computational model, first and foremost, but importantly it is an easily understood graphical notation for representing that model. A Petri Net is represented as a graph with two types of nodes: Places (represented with a circle) and Transitions (represented with a box or bar). Here’s a simple state transition from one state to another via a transition.

The edges of the graph can only be between places and transitions or vice versa. You can never draw an edge between two places or two transitions. In the example above is connected to and is in turn connected to .

Each place can have one or more ‘tokens’. The interpretation of having a token depends on several factors. I prefer to interpret having a token as ‘making some assertion or condition’. For example - a token in might mean ‘the user is on a call’. The absence of the token means that the condition does not hold - the user is not on a call. You mark the token with one or more dots inside the place, like so:

A transition is active _or _enabled if all places with edges leading _into _it have tokens. In this case is active because it has an input place () and has a token. There may be more than one input place to a transition.

In this case is not enabled, because not all of its input places have tokens. is missing a token. If you interpret the petri net as sets of conditions, then can be interpreted as ‘ and ’. If is the condition that the other end hung up, then can be interpreted as ‘the user was on a call and the other end hung up’. It’s a bit contrived, but you can see what I mean. If we placed a token in , then would be enabled again.

The complete set of tokens in places is known as the ‘marking’ of the Petri Net, and represents the current state of the system. Again, if you interpret it as a set of conditions, the markings represents the set of all things that you know to be true.

When an active transition ‘fires’, it takes one token from each of its input places and inserts one token in each of its output places. When the Petri Net fires, it performs a transition from one state to another. This can be thought of as representing the outcome of some computation or as the implication of what we know. If was something like ‘we are playing the dial tone’, then the whole above example can be interpreted as ‘if we are on a call and the other end hung up then we should start to play the dial tone’.

If we started with this

then firing would lead to this marking

A transition can have multiple outgoing places as well. Imagine another place , interpreted as ‘we go back onto the ready queue’. Then this model represents the assertion that if we’re on a call and the other end hangs up then we start playing the dial tone and we go back onto the ready queue.

Clearly we have the ability to represent complex propositions using a petri net. And some of the conditions might continue to hold after firing a transition as well. That’s easy too.

The observant amongst you will immediately notice that will always be enabled under this marking and the tokens will continue to grow. There’s a lot of techniques for analysing this kind of net and its properties. I can’t go into that topic here, but as with other software design, there are patterns and refactorings that can help to design a safe and conservative net.

The arcs of the Petri Net can, and generally are, ‘generalised’ to represent the case of multiple arcs between a place and transition. Rather than muddle the model with many identical edges we can add a ‘weight’ to an arc. Whatever the weight is, is the number of tokens removed or added. Whatever the sum of the weights on the input arcs are is the number of tokens that must be present in the input places for a transition to be active. Likewise, the output arcs of a transition can have weights signifying how many token they add to their output places.

For more information on the other extensions to the Petri Net rules, I recommend reading Murata’s paper.

OK. The preliminaries are over. That’s covered most of the rules for firing a Petri Net. I’ve not even scratched the surface of all the techniques for working out how a given Petri Net will behave. Petri Nets are popular in designing complex distributed systems, because they can be used to simulate the systems. I hope to show in later posts how we can take a runable model and use it not only for code generation and application glue, but for simulating the behaviour of our apps at runtime. If you want to know more, the following links will give you plenty of history, background and theory.

-

James L. Peterson. 1977. Petri** Nets**. ACM Computing Surveys, 9(3), September 1977.

-

Murata, Tadao. 1989. _Petri** ](http://www.cs.sysu.edu.cn/selab/references/TCS/T.Murata(IEEE1989)%20Petri%20Nets%20-%20Properties,%20Analysis%20and%20Applications.pdf)[nets](http://www.cs.sysu.edu.cn/selab/references/TCS/T.Murata(IEEE1989)%20Petri%20Nets%20-%20Properties,%20Analysis%20and%20Applications.pdf)[: Properties](http://www.cs.sysu.edu.cn/selab/references/TCS/T.Murata(IEEE1989)%20Petri%20Nets%20-%20Properties,%20Analysis%20and%20Applications.pdf)_[, analysis, and applications**. In Proc. IEEE-89, volume 77, 541–576.

Andrew Matthews

PROGRAMMING · SEMANTICWEB

CompSci Computer Science Petri Nets programming